Of all the changes occurring at Acconia, none have been more dynamic than the continual rise and fall of strawberry operations. Since its introduction to the area, the volatile crop has lured growers with its potential profits. However, success can be elusive. Those who do manage are able to contribute to what is a driving force of the town’s economy. Indeed, a strawberry festival is held at Acconia each year celebrating the fruit as locals see it become ever more central to their identity.

Of all the changes occurring at Acconia, none have been more dynamic than the continual rise and fall of strawberry operations. Since its introduction to the area, the volatile crop has lured growers with its potential profits. However, success can be elusive. Those who do manage are able to contribute to what is a driving force of the town’s economy. Indeed, a strawberry festival is held at Acconia each year celebrating the fruit as locals see it become ever more central to their identity.

Strawberries first entered Acconia’s agricultural landscape in the 1960s. Angela Gitto, who had come from Sicily a decade earlier, planted the first experimental plots in 1962 (around the house pictured right). She had acquired them from Ferrara and, taking notes on which variety grew best, found that the sandy soils and warm climate were just the right conditions for producing early strawberries. A couple years after these experiments, Mario Fattori arrived from Bologna and soon began growing as many as 30 hectares of the crop, sending the harvests north and making a fortune. Over the years, Fattori passed on his skill and expertise to those who worked with him and soon locals started their own operations.

Strawberries first entered Acconia’s agricultural landscape in the 1960s. Angela Gitto, who had come from Sicily a decade earlier, planted the first experimental plots in 1962 (around the house pictured right). She had acquired them from Ferrara and, taking notes on which variety grew best, found that the sandy soils and warm climate were just the right conditions for producing early strawberries. A couple years after these experiments, Mario Fattori arrived from Bologna and soon began growing as many as 30 hectares of the crop, sending the harvests north and making a fortune. Over the years, Fattori passed on his skill and expertise to those who worked with him and soon locals started their own operations.

The 1970s saw the rise of the small holders. The autostrada was officially completed in 1973 and drastically reduced travel time from Calabria to Naples and then on to Rome and northern Italy. This reduction opened up new markets diminishing transportation’s effect as a barrier to entry for new growers. Any farmer wishing to enter strawberry cultivation would still need to purchase land from one of the old families, however, most of whom would sell only a small plot if anything, or rent

public land, most of which was already in use. Fortunately, not much land was needed—strawberry cultivation required a single hectare or less. Once land was acquired, irrigation implemented, and the plants and other materials purchased, as long as the grower had household labor, they were able to turn a small profit. Profit was something new. Often these families had previously worked as colonos, tenant farmers, or mezzadros, sharecroppers, and so with strawberries were able to make a better living than they ever had done before.

Acconia’s strawberry fields did not grow unchecked.

One unexpected setback was the Chernobyl nuclear meltdown in 1986. The accident happened in April, at the height of Strawberry season, and closed down many markets throughout Italy. The large businesses had for the most part already sold their produce, but smaller holders with their limited labor were still in the harvesting process. When health officials shut down the markets, the small holders could not sell their goods, did not make back their investments, thus were unable to repay loans, and so failed. The few that did survive had not recovered even by 1989.

One unexpected setback was the Chernobyl nuclear meltdown in 1986. The accident happened in April, at the height of Strawberry season, and closed down many markets throughout Italy. The large businesses had for the most part already sold their produce, but smaller holders with their limited labor were still in the harvesting process. When health officials shut down the markets, the small holders could not sell their goods, did not make back their investments, thus were unable to repay loans, and so failed. The few that did survive had not recovered even by 1989.

In the 1990s, strawberries began to be cultivated in greenhouses rather than out in open fields as previously done. Early in the decade, a regional program helped cover the costs of purchase and installation for these greenhouses and they soon covered the landscape. They offered greater control over the growing conditions of the strawberries and as such allowed for even more intensive and efficient production. However they did not allow for the same level of flexibility in use being only suitable for strawberries or other forms of horticulture. While some growers with greenhouses wish to return to the open fields, most still see the structures as a symbol of the producer’s identity—a source of pride.

In the 1990s, strawberries began to be cultivated in greenhouses rather than out in open fields as previously done. Early in the decade, a regional program helped cover the costs of purchase and installation for these greenhouses and they soon covered the landscape. They offered greater control over the growing conditions of the strawberries and as such allowed for even more intensive and efficient production. However they did not allow for the same level of flexibility in use being only suitable for strawberries or other forms of horticulture. While some growers with greenhouses wish to return to the open fields, most still see the structures as a symbol of the producer’s identity—a source of pride.

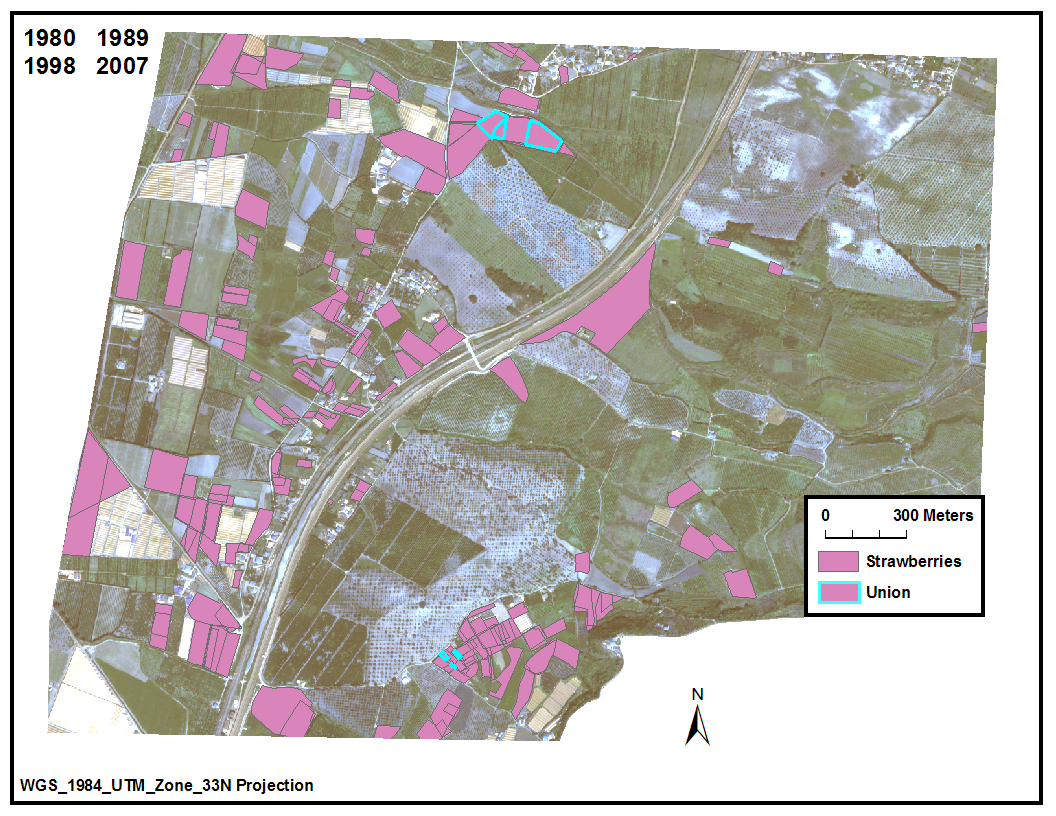

Since 2002, the Italian economy has been sluggish and the strawberry growers at Acconia have suffered. Middle class families in the country feel the pinch and no longer spend their money on the high-quality domestic fruits available to them, but rather seek cheaper options from abroad. Thus demand decreased. In the meantime, the cost of labor have increased and the prices of plastic sheeting, fertilizers, pesticides and fuel have risen. Under these conditions, the small family holdings have been unable to sell their products at market while the larger agro-businesses are buckling under expenses and wages. These stresses have put the future of strawberry production at Acconia in question. As seen in the map below, only six strawberry fields were present in each of the first four mappings. Is such intensive production sustainable? This brings to mind the title of a song by The Beatles, now it becomes the question: are strawberry fields really forever?